School Spending and Educational Outcomes

Education spending and student learning outcomes

- DAVID EVANS|JANUARY 17, 2019 World Bank Blog

Prior findings

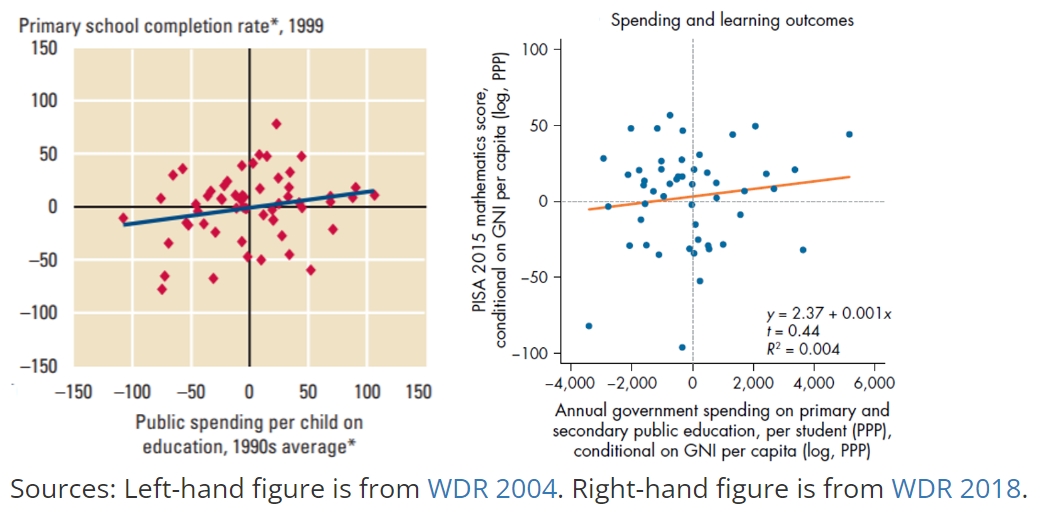

- World Bank’s World Development Report 2004 showed little correlation between spending and access to school

- World Development Report 2018 shows a similarly weak correlation between spending and learning outcomes

- Vegas and Coffin, using a different econometric specification, do find a correlation between spending and learning outcomes up to US$8,000 per student annually.

Does money matter? Yes.

[section copied from source]

Historically, most primary and secondary education was financed by local property taxes, so richer areas had better funded schools. But between 1971 and 2010, more than two dozen states had to reduce inequality in spending due to judicial decisions. This led to changes in school spending that were not related to other variables like local commitment to education that normally make it hard to parse out the link between financing and education. Using the variation in spending coming from the first wave of reforms, “a 10% increase in per pupil spending each year for all 12 years of public school leads to 0.31 more completed years of education, about 7% higher wages, and a 3.2 percentage-point reduction in the annual incidence of adult poverty. They also find that the effects are more pronounced for children from low-income families”.

A study of more recent school finance reforms finds that “a one-time $1,000 increase in per-pupil annual spending sustained for 10 years increased test scores by between 0.12 and 0.24 standard deviations”. Another study finds that in states with strong teacher unions, school districts tended to match increases in state funding, which “led to larger increases in student achievement”. Other work looks at the impact of these financing reforms on high school graduation rates: “Seven years after reform, the highest poverty quartile in a treated state experienced an 11.5 percent to 12.1 percent increase in per-pupil spending, and a 6.8 to 11.5 percentage point increase in graduation rates”.

Beyond school finance reforms, the Great Recession (2007 to 2009 in the United States) provides an additional natural experiment. State tax revenues fell much more suddenly than local or national revenues, so states that relied more on state revenues had a disproportionate drop in financing. Researchers found that “a 10 percent school spending cut reduced test scores by about 7.8 percent of a standard deviation”. Another study finds comparable results: “a 10 percent increase in spending improves…student test scores by 0.05 to 0.09 standard deviations.”

In sum, out of 13 multi-state studies, Jackson finds that 12 show a positive, statistically significant relationship between education spending and student outcomes. And remember: these aren’t just correlations. These are all studies that have tried to tease out the actual impact of spending on learning or attainment.

See Jackson’s review for discussion around dependency on how money is spent.

The Relationship Between School Funding and Student Outcomes

- aei : Adam Tyner , 8 Oct 2019

Visible Learning – Hattie

Further References

C Kirabo Jackson American Economic Journal Finance reforms Learning Policy Institute – report Countries outperforming Us beatty